Image by 4thebirds, Shutterstock

From rocks to reptiles, mammals to moths, or birds to bushes, there’s probably a guide book published for easy referencing while in the field. With pages of images and descriptions at hand, the nature observer can thumb through a pocket-sized reference (or app) to find myriad bits of information to help identify most every critter one might encounter.

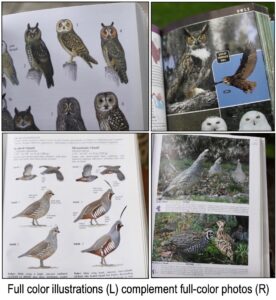

Still all guide books aren’t the same. Some emphasize extensive descriptions on the structures of a plant or the appendages on an insect or the subtle curve of the beak of a shorebird through differing amounts and thoroughness of information — most of which you don’t have time to read if you’re trying to make a quick ID of a fleeting bird on the wing. One of the best forms of identifying a bird, for example, is an image on a page — either illustrated or a close-up photo — of the bird in its natural setting.

And therein lies a problem: Illustrators typically rely on controlled lighting to capture natural, vivid colors when conveying plumage hues, patterns and markings. Audubon had the luxury of thoroughly inspecting and interpreting the colors on his famous artwork because his “models” were either captive or, more often, dead birds. He could study and replicate their colors quite accurately. Guide books that feature illustrations likewise reproduce colors on drawings that are ideal representations of the bird’s actual colors.

Trouble is, due to the glare of sunlight or the masking by shadows, those colors seldom look that way in the field. Reds don’t always appear red; yellows are not always yellow. Bright reds may appear a dull, dark brown; deep blues can appear black; some subtle tones, streaks and other markings may not show up at all. Carrying two field guides helps the observer compare textbook illustrations with real-life field lighting to compare colors and markings to help aid in a positive ID.

Here are a few other key observations on details your guide books should feature to help you determine what particular bird you are watching:

- Size: Use a bird or an object you are familiar with and compare its size to the bird you are trying to ID; the guide should list the bird’s height, wingspan, etc.;

- Shape: Body forms can be very subtle between species: Note the shape of the bill (straight or curved up/down?), long/short, pointed, blunt; leg length, body style, profile (crested, elongated head, etc.);

- Field Coloration & Markings: Eye color or a distinct ring around eyes, beak (light, dark, two-colored), striking patterns on wings, rump, neck, etc., color of underwings in flight, shape/size/distribution of coloration, spots or streaks on tail, wings, breast, head, etc.; (refer to both drawings and photos from both guidebooks if markings/colors are confusing — or to simply reaffirm a characteristic);

- Action/Antics: What’s its behavior as it moves around (hops, flitters, dips when it walks, has an arching flight pattern); tends to be alone or part of a flock;

- Habitat/Seasonal Presence: What environment is it in and what time of year is it? Some birds only appear in spring or fall, and some are only found in specific surroundings;

- Song or Voice: Distinct sounds can be diagnostic in identifying birds, either by unique/recognizable audible notes or in the pattern of their song.

A good field guide will have definitive information to help narrow down the suspects in your efforts to ID myriad critters, and in some cases, two is better than one.

It’s also good to have a third guide, a comprehensive reference bird book in your home library, to help determine or reaffirm your observations made in the field.

Tom Watson is an award-winning outdoor safety and skills columnist and author of guide books on tent camping, hiking and self-reliant survival techniques. His website is www.TomOutdoors.com.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The