Phil Short has done research for organizations such as the U.S. National Park Service, the U.K. Police Search and Rescue Service, and NASA.

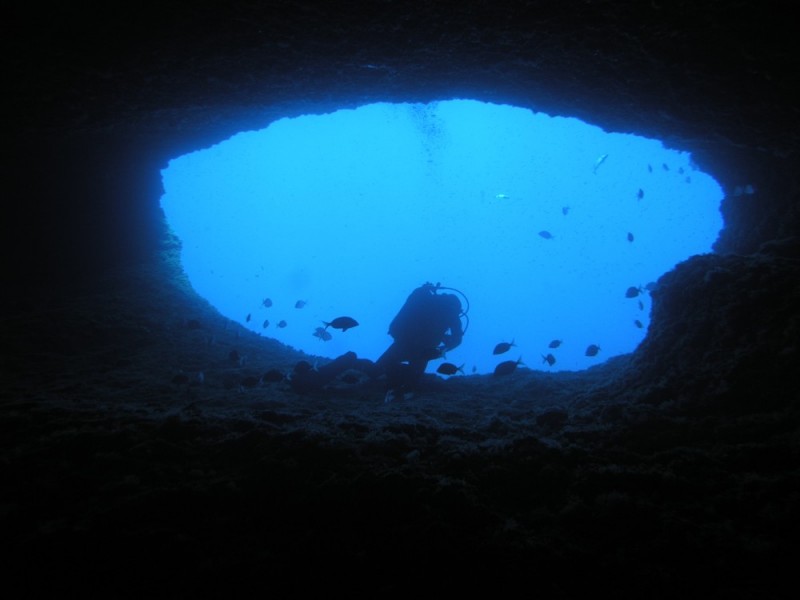

Phil Short is a technical diving consultant from the U.K. who has spent a total of 3,000 hours underwater carrying out his hobby of cave diving, as well as gathering data for scientific research. Author of a Q&A session with Short is Leslie Baehr, who works with six others from MIT writing for The Raptor Lab: Devouring Science, One Post at a Time.

Baehr said we live in a time where unmanned vehicles are used as the primary source of gathering scientific data from hard-to-reach places, such as in the depths Short is passionate about exploring. She said it’s exciting when humans are the ones in the field doing this “boundary-pushing research.”

Organizations such as the U.S. National Park Service and the U.K. Police Search and Rescue Service have employed the diver for his knowledge on data collection while underwater, specifically in training other divers to do the same type of research. Much of Short’s work has incorporated the use of rebreathers, which are more advanced than the traditional breathing apparatus used in scuba diving, because it absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user’s exhaled breath and recycles the unused oxygen in each breath. The traditional method, an open-circuit breathing apparatus, allows all of the exhaled gas to discharge into the environment.

“Generally the cave people—the scientists—don’t go there because it is a much more difficult, uncomfortable, unpleasant, and hazardous environment, so they tend to leave the acquiring of data to the speleologists [cavers], the people like myself who do it as a hobby,” he said. “But we are used a lot.”

Short recently returned from a trip to Mexico where he spent three months and 1,000 hours under the Earth in caves while being filmed for a Discovery Channel Curiosity episode.

“The project in Mexico was run by a guy called Bill Stone who works for NASA, so we were doing saliva samples for analysis of the effects of long-term sensory deprivation by being underground, on the immune system and things like that,” he said. “We quite often do water samples and life samples and all these other bits and pieces. So the scientists effectively use us as drones to go down and bring back what they need—measurements, data, samples, etc.”

Short said NASA is taking saliva samples before, during, and after being underground for a period of two weeks or longer to determine if there are changes in the body’s chemistry and makeup after going without sunlight. Scientists want to see if the body clock we are accustomed to alters underground, with specific regard to the immune system, which relates to long-distance space missions.

In a blog post on his website, Short joked that when he told people he only went caving five times during his entire three-month stay, they seemed shocked. He replied, “Not many! But once for 19 days, once for five days, once for 21 days, and two separate one-day trips, totaling over 1,000 hours under the Earth.”

In addition to cave exploration, Short has also spent time working for the Fisher Corporation, a treasure hunting firm, investigating the Atocha and Margarita shipwrecks from the 1600s in the Gulf of Mexico.

“A lot of the U.K. diving is wreck based, so it wasn’t something that’s completely new to me,” he told The Raptor Lab. “Cave is my passion, so to speak. That’s what I enjoy the most so I put my personal time into cave, but working on wrecks is pretty normal for this industry.”

For more information on Short’s expeditions, check out his website and keep an eye out this fall for a longer piece Baehr will write for Oceanus magazine that will include Short.

Image from Marco Busdraghi on the Wikimedia Commons

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The