It was late March in Alaska. We had just cut a hole through 20 inches of ice in the center of the channel on a river north of Fairbanks. As I was within arm’s reach of the alders growing beyond the steep banks at river’s edge, the ice suddenly fell away beneath me. Frigid water instantly gushed up around my legs. I lurched forward, clutched the nearest branch, and was able to twist myself sideways and back on to stable ice.

During winter’s shoulder season prior to spring thaw, adventuring onto what we hope is still safe ice can be a risky undertaking. A cardinal rule of ice is that it is never 100 percent safe.

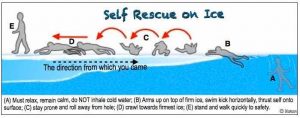

Breaking through the ice is a life-threatening experience — and being able to rescue yourself may be your only option for survival. Initiating this proven sequence of procedures may offer you the best chances at saving yourself:

- Stay “calm”: What that really means is to avoid inhaling cold water during the first moments of gasping for breath. Try to work through the initial physical/mental shock of breaking through the ice.

- Which direction to exit?: The only direction you know the ice will hold your weight is the direction you came from before you fell through. All other ice beyond or beside you could be unsafe. Always attempt your exit facing the direction from which you came.

- Leave your coat on!: Unless you have weights in your pocket, it’s best to leave on clothing, even bulky items as they contain air spaces that can help keep you buoyant.

- Get horizontal: You want to try to swim up and onto the ice, not pull straight up like doing chin-ups. Once horizontal, use swim kicking strokes to inch up onto strong ice (see the illustration below).

- Once out, stay prone and roll or crawl slowly away from the hole.

- Move towards safe ground and get dry and warm.

Some preparations and observations you can make for crossing over ice afoot include:

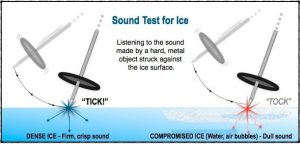

- Know how to “read” ice for best conditions: tap surface with metal ski pole tip and listen: a “tick” means ice is solid, firm; a “tock” means it could be weak or otherwise compromised (see the illustration below).

- Dull, dark, textured ice could be signs of deterioration.

- Carry a walking stick or use ski poles to be used to keep you from falling all the way through the ice or laid across the ice edge for support.

- Make sure fanny packs or bulging pockets don’t restrict you from sliding up over edge and onto the ice.

- Carry ice awls to help you “grab” onto ice as you pull/crawl forward.

- Always keep your arms out of water and onto ice (if you become weak or unconscious, your arms may freeze to ice, keeping you above water).

- Wear ice cleats for better traction and balance when traversing ice.

- Learn how to rescue others by presenting hand-holds such as branches, rope, ladder, ski poles, or walking sticks.

- Follow the safe routes made by others when practical.

- Leave some distance between travelers in case of a break-through (not always the first in line!).

Winter travel over ice makes our waterways accessible all year long, Like any outdoor pursuit, safety and proper preparation are key to any safe endeavor.

Tom Watson is an award-winning outdoor safety and skills columnist and author of guide books on tent camping, hiking and self-reliant survival techniques. His website is www.TomOutdoors.com.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The