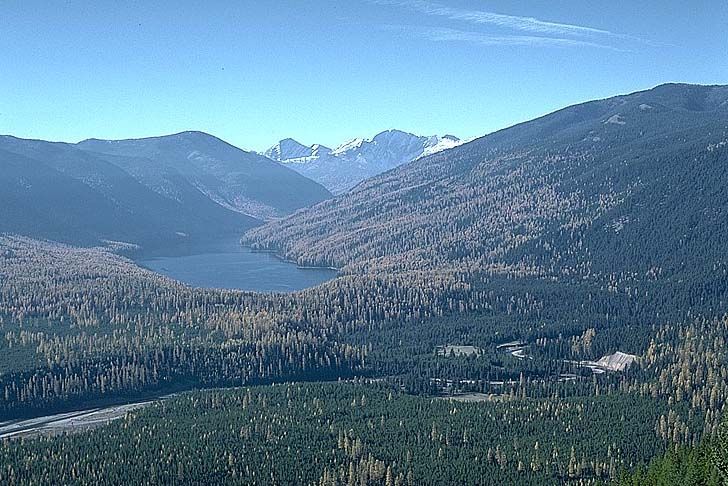

Montana's Bob Marshall Wilderness.

In 1998, my wife Jan and I mountain biked from Canada to Mexico along the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. The route led near, but not in, Montana’s vast Bob Marshall Wilderness.

In our couple’s parlance back then, we never really differentiated between forests, woods, and wilderness. They were all terms describing a bunch of trees, home to things that wanted to eat us.

But after mountain biking on some National Forest roads in western Montana we stumbled upon a ranger station and went inside for some information.

There, Jan informed the ranger we had just biked through the wilderness. Given the proximity to the Bob Marshall Wilderness, the ranger was very stern with us, criticizing us for pedaling in an area where cyclists didn’t belong.

It was then we realized the importance of the word wilderness, especially with agency types, and did a quick Emily Litella “never mind,” promising ourselves to never utter the words “mountain biking” and “wilderness” in the same sentence again.

Thank the Wilderness Act of 1964 for that. It’s been 50 years since its passage when millions of acres of federal land became protected under the National Wilderness Preservation System.

There are vast sections of forests and peaks with no mountain bikes or ATVs. Trail markings, signs, and bridges are fewer. Remote rescues take longer. Even geocaching is forbidden.

Those places are designated wilderness areas where self-reliance, challenge, and discovery rule.

Given it’s been around for a half century, it’s a good time to reflect on some of the wilderness areas I’ve been fortunate enough to pass through close to my northern New England home.

Vermont’s Green Mountain National Forest contains eight wilderness areas in 101,000 acres while the White Mountain National Forest has six wilderness areas totaling some 142,000 acres in New Hampshire and western Maine.

It’s in the rugged wilderness that remarkable natural beauty and splendid isolation is lost on the pavement of cities and suburbs a short drive away.

Logging railroads once chugged along the valley in Evans Notch along the New Hampshire-Maine border in the Wild River Wilderness, designated in 2006. This isolated area probably sees some of the fewest hikers in the Whites and includes the splendid low elevation Wild River loop, a roughly six-mile circuit through the hardwood valley on the Wild River and Highwater trails.

The Great Gulf Wilderness is the oldest (1964) and smallest (5,552 acres). With nearly three miles of the Appalachian Trail, the Great Gulf near Mount Washington sits in a glacial cirque among the majestic northern presidential peaks.

Like Wild River, the Pemigewasset Wilderness was once an active railroad forest. The Pemi is also the largest of the wilderness areas at 45,000 acres and contains the beautiful and remote 4,000-foot-plus Bonds.

The 35,800-acre Sandwich Range Wilderness is a delight with Whiteface, Passaconaway, and the Tripyramids in the house.

The 14,000-acre Caribou-Speckled Mountain Wilderness is entirely in Maine and was logged until the 1960s. Speckled Mountain with its lovely ledges (and blueberries) is the highest mountain in the area at 2,906.

South of Mount Washington, the 29,000-acre Presidential Range-Dry River Wilderness contains the Dry River valley, Oakes Gulf and Montalban Ridge with peaks like Mount Isolation and Stairs Mountain. The celebrated Davis Path, built in 1845 as the longest bridle path up Mount Washington, passes through the wilderness.

The Breadloaf Wilderness is Vermont’s largest at some 25,000 acres. Some five miles of the Long Trail/Appalachian Trail swing through the 6,700 acres of the Big Branch Wilderness. Its Baker Peak may be small at 2,860 feet, but the open summit has big panoramic views.

Parallel to Big Branch is the Peru Peak Wilderness. West of Landgrove, the 7,600-acre region contains about three miles of the AT/Long Trail that winds over the tops of 3,000-foot Peru and Styles Peaks. Those famous footpaths also snake through the northwest section of the 17,800-acre Lye Brook Wilderness east of Manchester Center for about four miles.

An observation tower stands atop 3,747-foot Glastenbury Mountain in the Glastenbury Wilderness (22,400 acres) outside Bennington. Some 15 miles of trails are maintained in the wilderness including the Long Trail.

East of Lake Champlain near Bristol is the Bristol Cliffs Wilderness, the smallest in the state (3,700). The 5,000-acre George D. Aiken Wilderness, named after the late Vermont senator, is without established trails on the often soggy, marshy area.

The 12,333-acre Joseph Battell Wilderness comprises Middlebury and Brandon Gaps and 3,000-plus footers like Monastery and Worth mountains. The land was once a gift from the nineteenth century publisher to Middlebury College.

It’s a wild gift that keeps on giving.

Image courtesy of U.S. Forest Service/Wikimedia Commons

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The