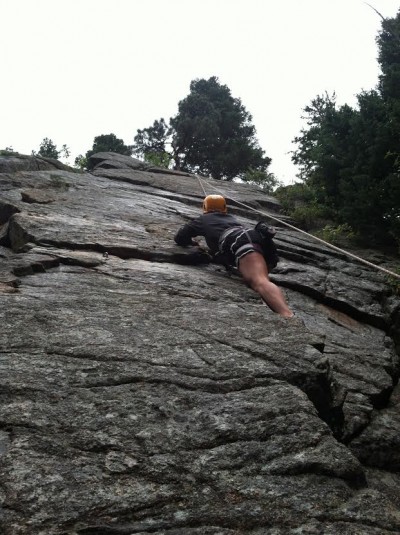

Climbing The Watermark slab in Boulder Canyon.

The sweat that forms on the forehead of a climber sending a route is almost identical to that of a yogi at the end of a strenuous practice. The two activities—yoga and climbing—go hand in hand.

The transition from hands in chinmudra to chalk-covered knuckles is almost seamless, and the basics of each can be reduced down to simple concepts. Yoga increases flexibility and climbing builds strength. These skills are being used almost constantly during both practices.

There’s a reason that climbers like Alli Rainey, Chris Sharma, and Lizzy Scully have adapted both practices as part of their lives. There’s a reason that outdoor companies like Prana and Moosejaw carry products for both activities: they complement one other and provide immense benefits.

In a video by Prana Living, climber Chris Sharma takes on yoga at the Wanderlust Festival in Squaw Valley. In the video, Sharma struggles with poses and even coins himself a “beginner.”

“I think yoga can really enhance one’s experience climbing,” he said in the video. He explains that climbing is a little more agro, “Inviting the animalistic side of nature,” he continued.

Climbing requires, as much as it builds, quite a bit of strength. The sheer act of pulling your body up a slab of rock takes a lot out of your muscles. These aren’t running muscles, they aren’t baseball muscles, and they aren’t even yoga muscles.

Of course, any bit of strength training helps, but only more climbing will build exactly what it takes to climb a little higher, and maybe send a route instead of pulling through after a fall. The more you climb, the better a climber you will become.

“You need the muscle tone that comes with climbing,” said Lori Frederickson, an avid climber of Mount Pleasant, Michigan.

Flexibility and balance combined are just about as important as strength is, though.

Climbing can, and often does, involve throwing your foot up as far as you possibly can, and no doubt that a little extra hip flexibility helps. The art of the reach is constantly challenged in climbing, and it applies to every limb.

Balance is core to climbing as well. Without it, movements can easily become stiff and will only lead to a fall. Body awareness and positioning can mean the difference between reaching the top of a climb and taking a fall. On harder routes when reliable footholds are more difficult to find, the ability to balance on a small crevice can make all the difference.

Yoga instructor Mary Beth Orr inverting herself on Mount Elbert in Colorado. Photo courtesy of Mount Pleasant Hot Yoga.

A combination of aerobic and anaerobic endurance is also necessary to a healthy climbing practice. Aerobic endurance, what most people are familiar with, is being able to perform the same task for several minutes while the body utilizes oxygen. Anaerobic endurance is the opposite—the body does not utilize oxygen to perform the task at hand. Often these exercises are two minutes or less, more intense, and build muscle mass quicker than an aerobic exercise.

Climbing is easily characterized as a combination of aerobic and anaerobic. Taking 10 or 15 minutes to scale a wall classifies as aerobic exercise, but the problems and small challenges that involve bursts of energy in between become anaerobic.

Yoga involves many of the same skills, but the most obvious difference between the two practices is the switch from vertical to horizontal, and the end result.

With climbing, the goal is always to reach the top of the wall, to send the route, to climb higher and harder. Yoga is a bit different, and although the fundamentals are taught in unique ways all over the world, yoga is never about competition.

“Yoga practice seems very much focused on finding this balance within yourself, within nature,” Sharma said.

The word yoga means “yoking” in Sanskrit, which has come to mean yoking the mind and body together. The practice itself can take on a different form for anyone who gives it a try, easily forming to different goals or intentions.

Cathryn Kruger, an avid yogi of Huntington Beach, California, sets personal goals for posture so she always has something to work toward.

It isn’t all meditations and intentions though, although they play a huge role. Strength is important for hitting certain poses, particularly inversions and acro yoga. Core strength is extremely important for maintaining form while getting into and remaining in inversions.

“It’s mainly core strength with a little bit of leg,” Kruger said. “It’s a lot less arm strength than people think. It’s more about bone alignment and weight distribution.”

Flipping your body from feet on the floor to in the air takes muscles that are built best by trying poses and challenging yourself in your practice when you feel comfortable.

Whereas climbing has routes that indicate difficulty, in yoga, the yogi determines the difficulty. The person practicing, instead of where the wall ends, determines the end of practice. The person can choose the poses instead of a wall giving you few options.

Physically, the most difficult thing for Kruger is knowing her limits and boundaries, and when she has gone too far. Even with full control over your practice and the poses done, knowing when to stop pushing yourself can be difficult.

Yoga is known for inducing a meditative state, but this is also evident in climbing.

Hilary Young of Ann Arbor, Michigan has been climbing for 15 years and doing yoga for about 10. She said she finds the meditative state is more easily reached through climbing.

“Climbing and yoga have a lot of similarities with focused attention,” she said. “You really can’t think about anything else except that thing that you’re doing.”

On a yoga mat, some poses might be more physically challenging, but being 50 feet up, hanging by a rope renders a different sense of focus.

“With yoga, it’s a choice to have that focus and let other things go, and it’s not easy to do,” Young said. “But with climbing, you’re pushed so much physically, it literally cannot happen without it.”

This focus that Young talks about is the same focus that yoga strives for—undivided attention on the present.

Yoga deals with a lot of breath work, as well. The techniques that are used during a yoga practice can easily be applied to a climb. Young uses what she’s learned from yoga breathing and applies it when she climbs, in terms of not holding her breath.

One look down off a tall rock wall can make a climber extremely nervous, which often leads to them holding their breath, eventually preventing enough oxygen from reaching the brain. By applying breath work techniques learned in yoga to tight situations in climbing, it can be the difference between freezing up and keeping on.

Yoga and climbing work hand in hand with each other, taking strength built from climbing and applying it to yoga. The techniques and mindset that yoga can instill in a person can be directly applied while on the rock wall.

Both activities are extremely good for your health, both create a sense of calm and focus, both share similar cultural aspects, and are often popular in the same areas.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

The

The